One town called Rendville became different from the other coal mining towns in Southeast Ohio because of the racially mixed community of African American and European immigrant miners. Rendville was one of the first integrated coal mining towns in Ohio. Rendville was established in 1879 by Colonel William P. Rend, an Irish-born industrialist from Chicago who hired African Americans to work alongside European immigrants within Rendville, which was unusual in the late 1800s and early 1900s. “I [found during] my research that Rendville, at the time, was called a sociological experiment because it would not place at that time where blacks and whites were living, working, and worshiping peacefully together,” said Cynthia Preston, Assistant Professor at Ohio State University. However, many miners from white neighboring towns were against this practice because they thought hiring black workers to work in the mines would bring down wages. Still, Rend advocated for his miner's rights and later founded and incorporated Rendville in 1882.

As the town grew in population as an interracial community, violence within the city progressed to a hanged lynching by a mob to avenge the murder of a resident on February 3, 1884, and rising tensions from other neighboring towns who started mobs who were against black men working in the mines. According to Urban Appalachian Community Coalition, in 1888, mobs of white mine workers from Corning and other nearby towns descended onto Rendville to drive out the black coal miners and their families from the Sunday Creek Valley. The mob hid weapons in wagons, but there was no bloodshed or intense violence that occurred because Governor Charles Foster called the National Guard to disperse the mob, and this would be called the “Corning War.”

Within Rendville, it was home to prominent figures in American history who have been unacknowledged. Richard L. Davis was one of the many African American miners from the Kanawha and New River region hired by the Ohio Central Coal Company and Colonel William P. Rend to work in the coal mine in Rendville when Rendville was established in 1882. He was also a leader in the Knights of Labor and one of the labor organizers who helped found the United Mine Workers of America in 1890. Along with Davis, Dr. Isaiah Tuppins was the first mayor of Rendville and the first African American to be elected as mayor and receive a medical degree in Ohio in 1888. In 1969, Sophia Mitchell became the first African American woman to be appointed mayor of Ohio. In 1953, Roberta Preston was the first African-American woman to become a postmaster in the United States and Ohio. Rendville was a bustling interracial community that thrived during the era of coal mining in Southeast Ohio until the closure of the coal mines in the 1930s - 1940s.

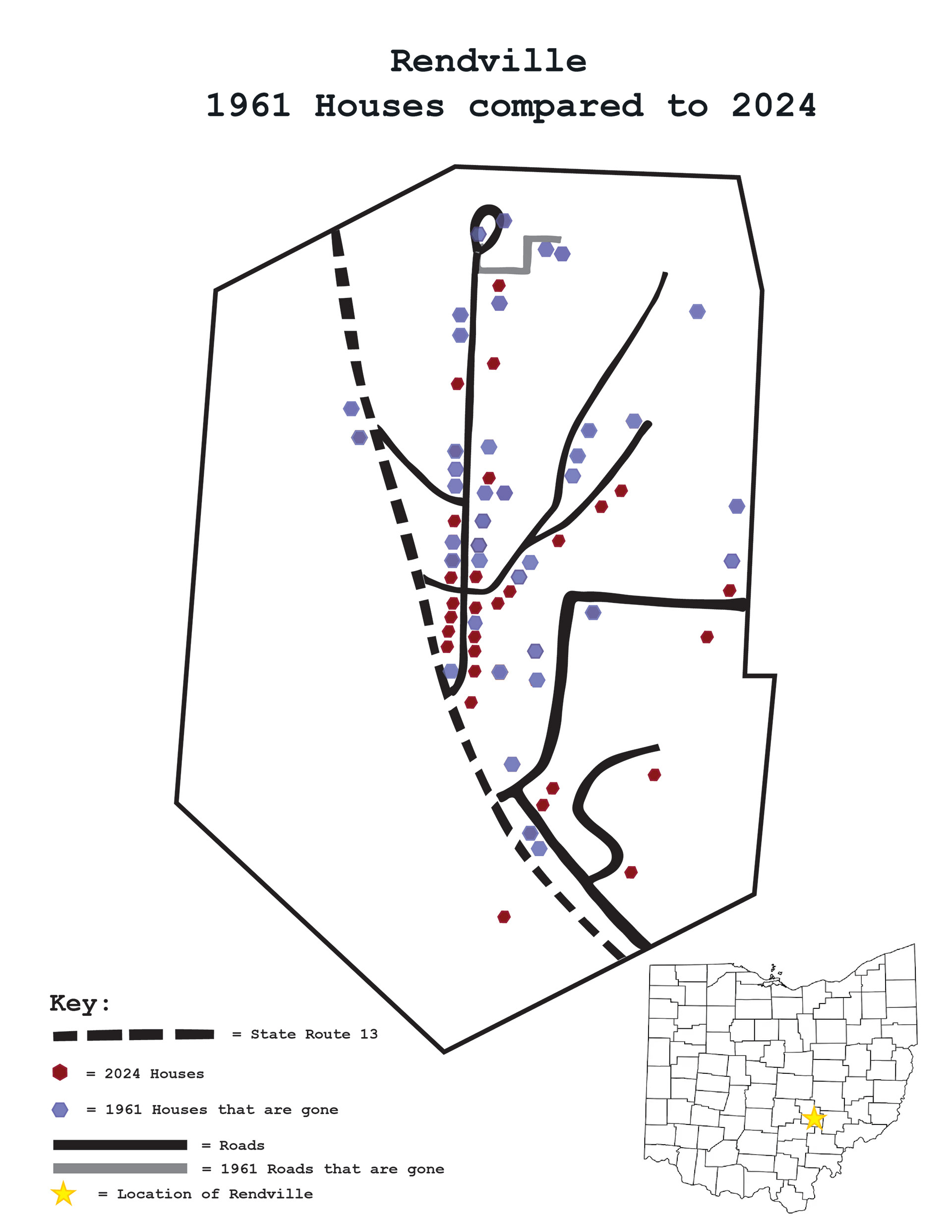

As the ‘Little Cities of Black Diamonds’ relied on coal mining for their infrastructure and economy, their populations decreased as residents moved out after the mines closed. The town’s economy also suffered and ceased to exist with no residents. According to the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census, Rendville had a population of 859 in the 1890s, 790 in the 1900s, 623 in the 1910s, 515 in the 1920s, 387 in the 1940s, 301 in the 1950s, and in 2024, there is currently 10-20 residents left in Rendville. Many residents have commented on how everyone got along with the town with no prejudice against the other to this day. The town is no longer incorporated as a town in Ohio and is considered a village claimed by the Monroe Township in Perry County.